On January 15th, an underwater volcano by the name of Hunga Tonga–Hunga Haʻapai erupted in the country of Tonga, a collection of islands located in the Pacific Southwest.

On January 15th, an underwater volcano by the name of Hunga Tonga–Hunga Haʻapai erupted in the country of Tonga, a collection of islands located in the Pacific Southwest.

It was the most powerful eruption in decades, causing a tsunami that wrecked many parts of the islands, and smaller tsunamis that struck other shores. Three people died from the impact and the region has suffered nearly $90 million in damages

The eruption even led to the formation of a temporary baby island nearby. Scientists are calling it “absolutely unique” and report that they have seen nothing like it!

Impact Of Eruption

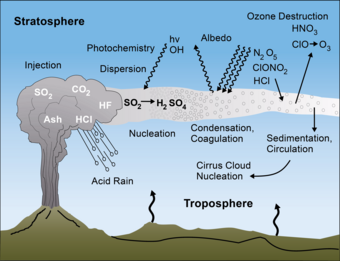

Usually, when a volcano erupts on land, it releases a much smaller amount of water vapor and more sulfur dioxide gas into the atmosphere. Sulfur dioxide has a cooling effect that lasts a few months.

The Hunga Tonga–Hunga Haʻapai volcano, however, is a submarine volcano. Given the scale of the eruption, it sent a record-breaking amount of water vapor 17 miles into the stratosphere! Scientists believe this is because the hot magma interacts with water to create a massive plume of water vapor.

Since water vapor is a greenhouse gas, it traps heat in the atmosphere and causes a slight warming effect that might take years to dissipate. This abnormal amount of water vapor could also heavily influence the chemistry of the atmosphere, boosting reactions that could worsen the ozone layer depletion, the part of the stratosphere that protects the Earth from harmful ultraviolet radiation from the Sun.

Since water vapor is a greenhouse gas, it traps heat in the atmosphere and causes a slight warming effect that might take years to dissipate. This abnormal amount of water vapor could also heavily influence the chemistry of the atmosphere, boosting reactions that could worsen the ozone layer depletion, the part of the stratosphere that protects the Earth from harmful ultraviolet radiation from the Sun.

Additionally, the eruption was so tremendous that it sent a shockwave across the globe, something that hasn’t been seen in half a century. The shockwave occurred because of the large amounts of energy released by the eruption that caused the air to compress and generate a pressure wave.

Opportunity For Scientists

Using images from drones and other instruments, scientists estimate that nearly 10% of the normal water vapor in the atmosphere was ejected on that single day, enough to fill 58,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

This unusual eruption will help scientists study the impact of greenhouse gases to better predict the weather and changing climate, the interaction of water and lava, and much more. Even now, eight months after the eruption, scientists and researchers are still studying this phenomenon and will continue to do so over the coming years.

Sources: NY Times, NASA, NPR, Science Daily