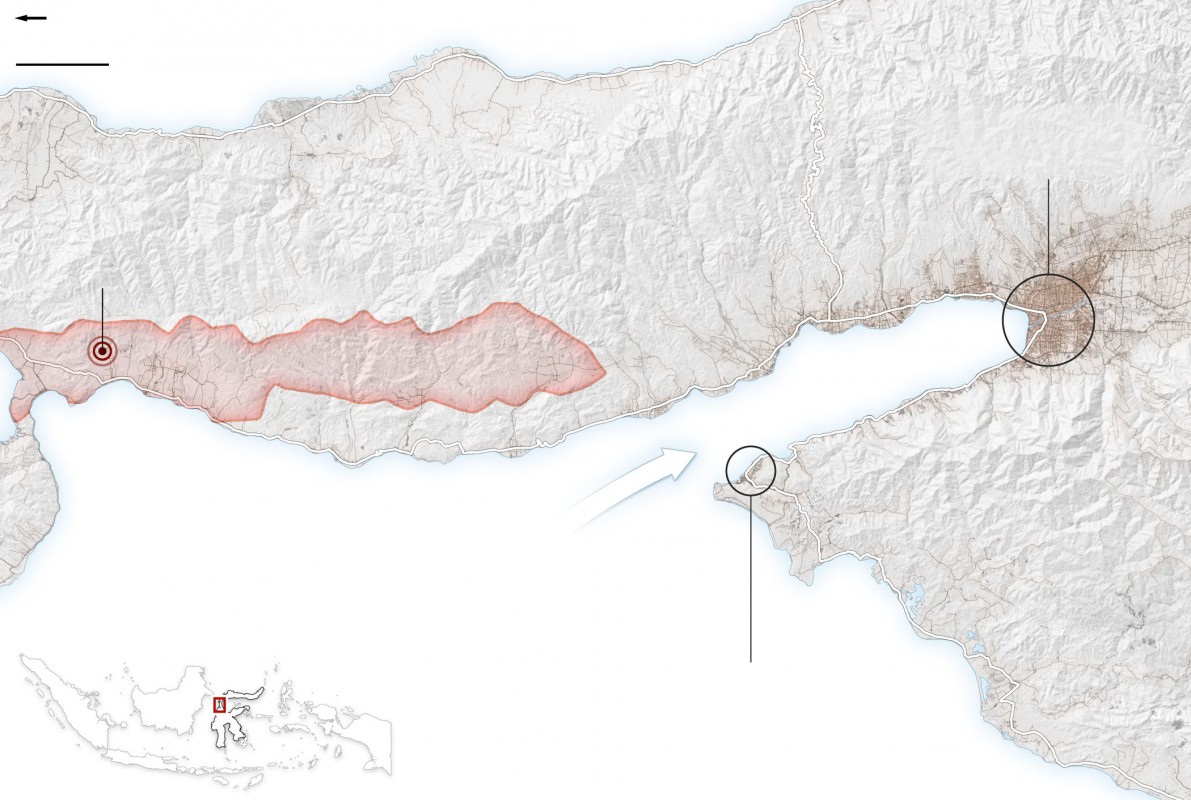

On September 28, a 7.5 magnitude earthquake occurred on the Palu-Koro fault located on the island of Sulawesi in Indonesia.

On September 28, a 7.5 magnitude earthquake occurred on the Palu-Koro fault located on the island of Sulawesi in Indonesia.

Shortly after, a tsunami struck the city of Palu, located about 50 miles away (see article here on how tsunamis form). These two events destroyed large parts of Palu as well as neighboring cities and tragically killed over 1500 people.

Let’s take a look at the science behind what happened. For a background on what causes earthquakes, click here.

When Soil Turns Liquid...

Palu and its neighboring cities are situated in a flat valley where the soil is loose and sandy and there is a high water table (water under the ground). The shaking of the earthquake caused a sudden stress on the soil, which in turns lost its strength and became almost like a liquid (a phenomenon known as soil liquefaction)

Think of when a wave washes onto a beach – the stress of the wave causes the sand under your feet to become very soft and it’s hard to stand. After the wave recedes, the sand will regain its firmness again. Similarly, buildings rely on the strength of the soil underneath them and will tilt or collapse during liquefaction.

Think of when a wave washes onto a beach – the stress of the wave causes the sand under your feet to become very soft and it’s hard to stand. After the wave recedes, the sand will regain its firmness again. Similarly, buildings rely on the strength of the soil underneath them and will tilt or collapse during liquefaction.

In addition, the water mixed with soil created flows of fast-moving mud and sludge, sweeping away buildings and buckling roads in their paths. Videos taken during the immediate aftermath of the earthquake showed buildings sliding sideways in these torrents.

Unexpected Tsunami

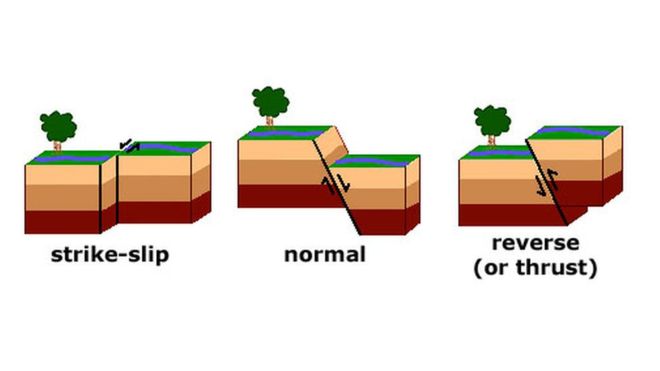

The tsunami that struck Palu was reported to be over 5 meters (16 feet) tall. Scientists have been surprised because tsunamis are not typically associated with earthquakes caused by strike-slip faults like Palu-Koro. Strike-slip faults are fractures where two rock plates move horizontally against each other in opposite directions.

The tsunami that struck Palu was reported to be over 5 meters (16 feet) tall. Scientists have been surprised because tsunamis are not typically associated with earthquakes caused by strike-slip faults like Palu-Koro. Strike-slip faults are fractures where two rock plates move horizontally against each other in opposite directions.

Usually, most large tsunamis occur due to megathrust earthquakes caused where a tectonic plate slides below another and one plate suddenly lurches upwards, pushing a large volume of water up (see image on right).

Even though tsunamis are not common with strike-slip fault earthquakes, they do occasionally happen. One primary way is when the shaking from the earthquake causes landslides, both above or below ocean level. Whether landslides start above water and then fall in, or they start completely below water, they too can display a large volume of water.

In addition, the shape of Palu Bay might have played a part in the force and size of the tsunami. As the the waves are squeezed through a gradually narrowing channel, they could have become stronger and higher, until they hit Palu which is located at the end of the bay. Scientists will continue to study the disaster site for clues to what happened. There is still much that we don’t understand of our earth’s tectonic plates and the effects of their movements.

Sources: Guardian, CNN, Scientific American, BBC, NYTimes, abc.net.au