As temperatures increase, we are already starting to see some bird and animal species move to cooler areas.

As temperatures increase, we are already starting to see some bird and animal species move to cooler areas.

When species migrate, they come in contact with new species for the first time -- and these encounters may not be as benign as you think.

Animals carry viruses, and when new species meet each other, viruses could jump between them as well as to humans. Let's find out more.

How Viruses Move

Viruses depend on their hosts (also known as vectors) to move to new places and to new species.

Consider insect vectors such as ticks and mosquitoes -- ticks carry Lyme disease and mosquitoes carry deadly Malaria and Zika viruses. These insects need hot and humid conditions to survive and breed. Due to global warming, Earth's average temperature has risen more than 1.1°C above pre-industrial temperatures. As a result, previously cold areas have now become warmer, allowing disease-carrying insects to expand their range.

Image Source: Sadie J. Ryan, Colin J. Carlson, Erin A. Mordecai, and Leah R. Johnson; Credit: Koko Nakajima/NPR

However, while insects thrive in the heat, other animals and birds are shifting toward cooler poles or higher up on mountains. While shifting their natural territories, species that have never met before would be forced together, allowing viruses to infect new hosts. When viruses cross over from one animal species to another, it is known as spillover. And when they end up jumping to humans, it is known as a zoonotic transmission.

Impact of Study

For the study, scientists examined more than 3,000 mammal species and the viruses they carry. By modeling the animals' movements, they estimated more than 4,000 possible new viral transmissions in a warming world.

Results show that the tropical regions of Africa and Southeast Asia will be more prone to new virus outbreaks. These areas have diverse ecosystems, large populations of animals, as well as dense human populations, all of which could prove to be breeding grounds for viruses.

Results show that the tropical regions of Africa and Southeast Asia will be more prone to new virus outbreaks. These areas have diverse ecosystems, large populations of animals, as well as dense human populations, all of which could prove to be breeding grounds for viruses.

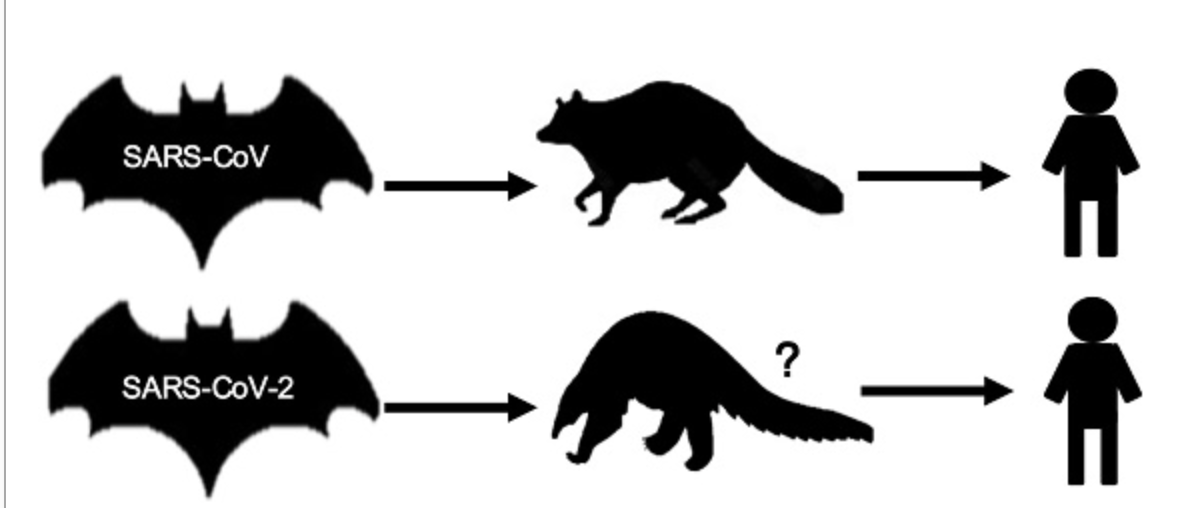

Scientists also expect that bats could likely be the cause of future outbreaks as they can easily fly to newer habitats and infect other species. Bats have already been identified as the cause of severe outbreaks in the past, such as a coronavirus that caused SARS in 2002. In that case, a virus jumped from the Chinese horseshoe bats to raccoons, and then to humans. Even the current COVID-19 pandemic has its origin in bats.

Predicting the exact range of animal migrations is difficult. Nevertheless, this study urges health officials and policymakers to strengthen the ability to detect disease outbreaks and make our healthcare systems more resilient.

Sources: Nature, NYTimes, PNAS, The Verge