In February and throughout the summer of 2024, the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) recorded the fifth mass bleaching event in the Great Barrier Reef since 2016.

In February and throughout the summer of 2024, the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) recorded the fifth mass bleaching event in the Great Barrier Reef since 2016.

In 2023, a record marine heatwave caused one of the worst coral bleaching in the Northern Hemisphere.

Yet, 90% of young coral in the Caribbean survived. As it turns out, the young corals had been bred using in-vitro fertilization (IVF)!

Let's find out more.

Hope for Corals: The Caribbean Study

Corals are crucial to marine biodiversity and support a quarter of all marine creatures. Humans depend on corals for food and protection from strong waves and storm surges.

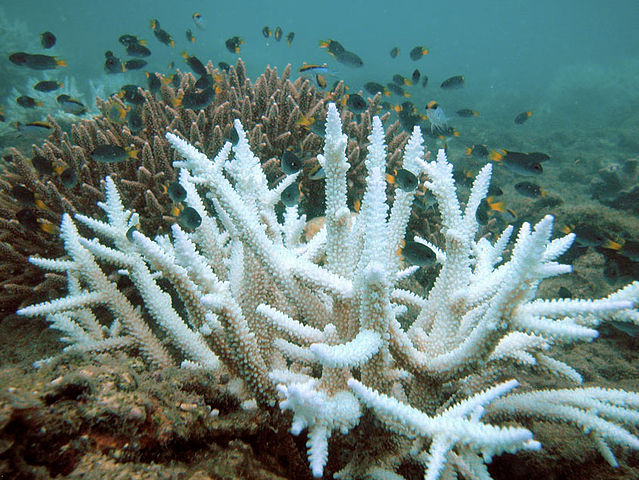

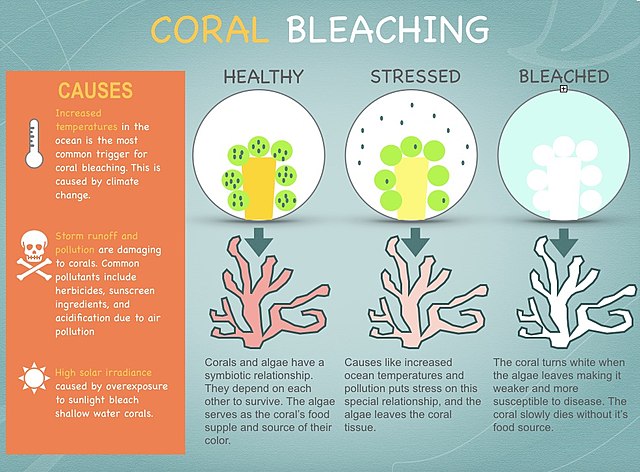

However, corals are also very susceptible to their environment: sedimentation, pollution, ocean acidification, and physical destruction by fishing, all pose threats to corals. But global warming is one of the largest challenges they face, causing corals to bleach (turn white). Learn about corals and bleaching in our earlier article here.

A recent study examined the impact of the 2023 heatwave on Caribbean coral and found that most young IVF corals remained healthy. These corals were bred in the lab and then planted in wild reefs, and while 75% of old corals had bleached or paled, 90% of young coral survived.

A recent study examined the impact of the 2023 heatwave on Caribbean coral and found that most young IVF corals remained healthy. These corals were bred in the lab and then planted in wild reefs, and while 75% of old corals had bleached or paled, 90% of young coral survived.

Usually, coral restoration techniques involve breaking corals into smaller pieces and transplanting them to other areas. While these transplanted corals are clones, IVF corals increase genetic diversity as they produce new baby corals. The different genes might allow corals to adapt by giving natural selection new traits to act on.

Scientists are not sure of the explanation for the difference in survival rates but have come up with multiple hypotheses, including that younger corals are more exploratory of different zooxanthellae algae. However, research suggests that they too will become less tolerant as they age.

Hope for Corals: Selective Breeding

Meanwhile, Australian scientists under Annika Lamb at AIMS are breeding more heat-tolerant corals.

Meanwhile, Australian scientists under Annika Lamb at AIMS are breeding more heat-tolerant corals.

They have ranked 25 corals from most to least heat sensitive, and on the one night a year that the corals breed, they mix and match to create different combinations of corals. This process is known as selective breeding. By using selective breeding, Lamb and her team are trying to speed up the process of natural selection to match the pace of changing temperatures.

Once global warming hits the 1.5C threshold, corals are not expected to survive. These effects can already be seen with the intervals between bleaching periods becoming shorter.

While these two studies give us new hope for corals, they are not the fix-all solution. "We cannot just keep making the climate warmer, and it will all be okay because we can bioengineer everything," reasons principal researcher Madeleine van Oppen at AIMS.

Super corals can help corals survive and adapt, they are an intermediate solution. The real fight remains in addressing the root cause: global warming and climate change.

Sources: NPR, Guardian, EPA, WWF, National Geographic