With the beginning of spring, not all of us may be looking forward to plants growing and flowers blooming. After all, this annual explosion of flora also marks the beginning of allergy season.

With the beginning of spring, not all of us may be looking forward to plants growing and flowers blooming. After all, this annual explosion of flora also marks the beginning of allergy season.

Nearly 30% of Americans suffer from seasonal allergies, often triggered by pollen from trees, grass, and weeds. For this section of the population, the coming of spring means more headaches, itchy eyes, and runny noses.

A recent study by researchers at the University of Michigan found that climate change is prolonging the allergy season. In fact, if current levels of carbon emissions continue, the U.S could see a staggering 200% increase in pollen over this century!

So how does climate change affect pollen, and what might we expect for future allergy seasons? Let’s take a closer look.

Climate Change – A Pollen Booster

In their study, the researchers discovered that warmer temperatures and rising carbon emissions have the largest impacts on pollen. To determine this, they analyzed historical pollen data and predictive climate models.

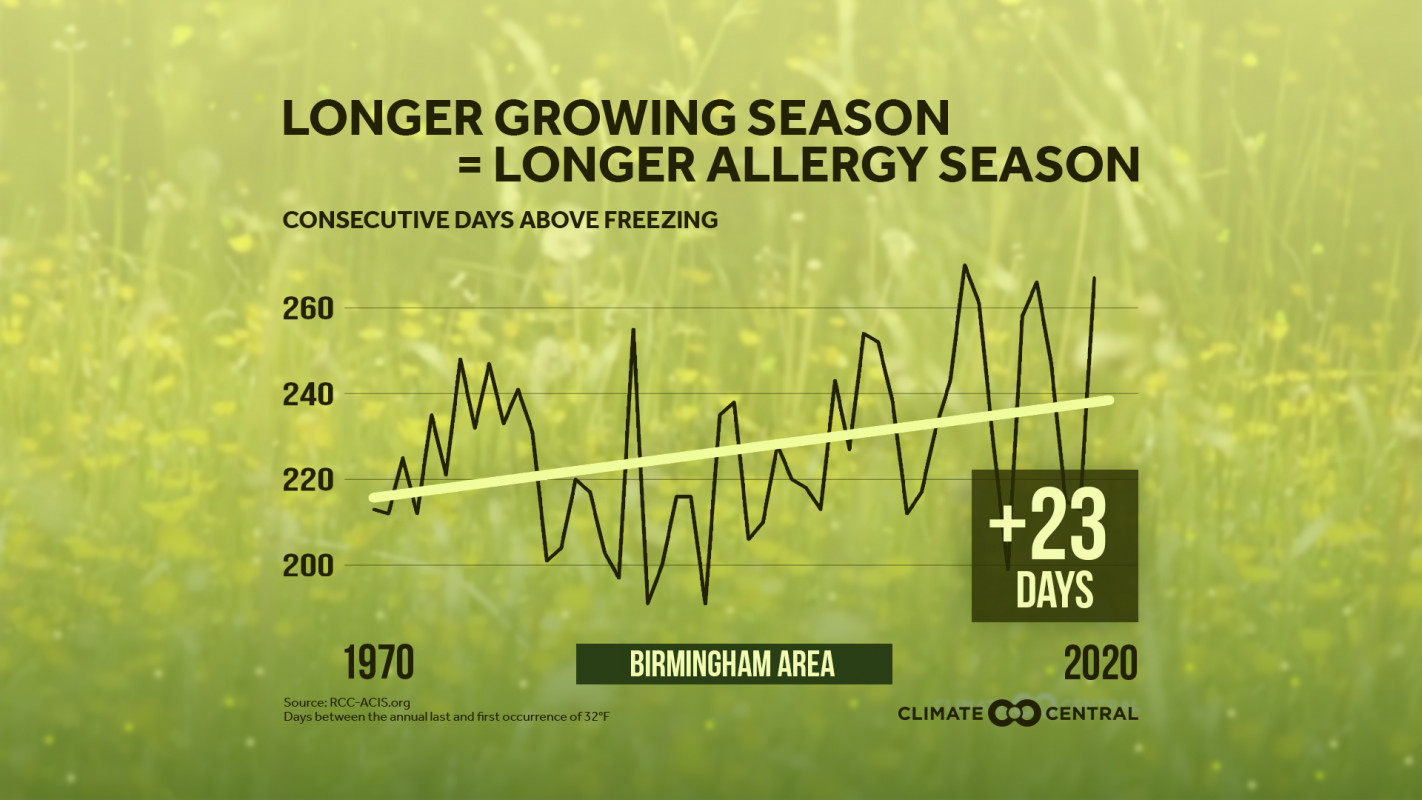

The researchers then used these tools to construct a model of possible allergy seasons over the next few decades. In the worst-case scenario, if current levels of carbon emissions continued, allergy seasons could be longer by a staggering 30 days! In a moderate scenario, where global temperature rise was kept below 3 degrees Celsius, the allergy season would still be extended by 10 days.

Why is this the case? The researchers found that hotter temperatures and precipitation encourage plant growth. This makes spring arrive earlier and lengthens the growing season. At the same time, the extra carbon dioxide from the burning of fossil fuels stimulates plant growth and the production of pollen.

Prepare the Tissue Box!

The researchers found that Northern states will experience more drastic allergy seasons, as they are the regions projected to see the most warming.

The researchers found that Northern states will experience more drastic allergy seasons, as they are the regions projected to see the most warming.

In addition, warmer temperatures are blurring the pollination seasons of allergenic plants. Usually, deciduous trees like birch and oak start in the late winter and spring, while grasses and weeds emerge in the summer. Now, these seasons are expected to overlap, releasing even more pollen into the air.

The allergy season is already 20 days longer than it was in 1990, and pollen concentrations have increased by 21%. This could significantly impact those who already suffer from asthma and outdoor allergies, as well as more people may develop allergies. This, in turn, could lead to high medical costs and absences from work and school.

Researchers hope their study’s model could help bolster pollen forecasting. At present, pollen forecasts are limited to a few regions as sampling different types of pollen is tricky and time-consuming. They are also planning more research into other types of plants, carbon dioxide levels, and pollen anomalies across growing seasons.

Sources: The Conversation, NBC, WebMD, AAFA.org