After a century of research, a malaria vaccine has finally been approved by the World Health Organization (WHO).

After a century of research, a malaria vaccine has finally been approved by the World Health Organization (WHO).

Malaria is a deadly disease with an annual death toll of 400,000. Many of the victims live in developing countries such as Africa. The disease is especially lethal among young children -- in 2019 alone, 260,000 children under the age of five died from malaria.

Now, Mosquirix, as the new vaccine is called, could help eradicate malaria and reduce child mortality. Let's find out more and why this vaccine could be important in the face of changing climate.

What is Malaria?

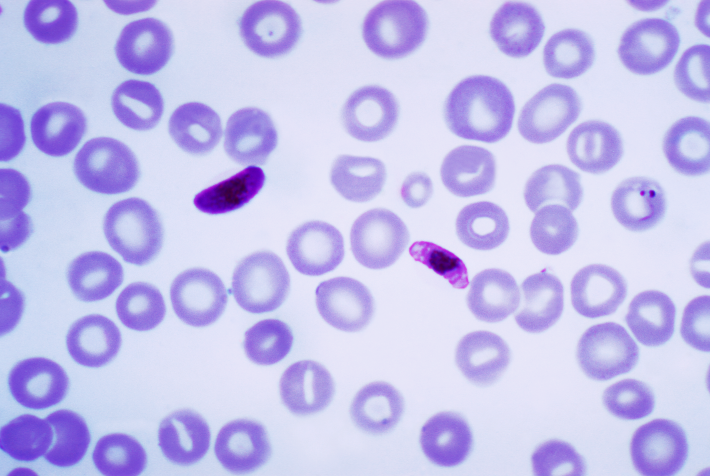

Malaria is a disease caused by a parasite, an organism that can only survive by living off a host animal. Mosquitoes are the main carriers of disease and pick up the parasite when they feed on the blood of infected people. The infected mosquitoes then transmit malaria by biting healthy people.

Once the parasite enters a person’s bloodstream, it releases spores called sporozoites. These sporozoites travel into the heart, lungs, and liver and infect red blood cells.

Once the parasite enters a person’s bloodstream, it releases spores called sporozoites. These sporozoites travel into the heart, lungs, and liver and infect red blood cells.

While death and severe symptoms can be prevented, the disease often causes irreversible damage to the immune system. Symptoms are often similar to the flu, but in severe cases, malaria can cause organ failure, seizures, and brain damage.

The road to preventing the spread of malaria has been challenging due to the disease’s complex nature. Malaria has evolved countless times alongside the human population and the virus possesses a large set of genetic materials. In fact, while the COVID-19 virus can code for 29 proteins, plasmodium falciparum, one of the deadliest parasites that cause malaria, can code for over 5,000!

Malaria and Climate Change

As climate change sees increases in global temperatures, tropical diseases like malaria are on the rise and are spreading to new regions. A rise in humidity and rainfall provide the perfect breeding grounds for mosquito populations.

In areas where malaria-carrying mosquitos already thrive, warmer temperatures can cause them to mature faster. This accelerates mosquito life cycles and increases the risk of malaria transmission.

Impact of the Vaccine

Mosquirix was developed by pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), which began trials in the 1980s.

Mosquirix was developed by pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), which began trials in the 1980s.

Adults who have been previously infected are less prone than children to more serious forms of malaria. Mosquirix was thus designed to protect children until their immune systems are strong enough to fend off malaria.

Mosquirix has already been incorporated into regular immunization programs in three countries in Africa: Kenya, Malawi, and Ghana. Three doses of the vaccine are given to young children between the ages of 17 months and age 5, followed by a fourth dose 18 months later.

The results have been modest. Only 30% of vaccinated children in the 2019 clinical trials did not develop serious symptoms. However, combined with current preventive measures such as insecticide-treated bed nets, Mosquirix is our best defense yet against malaria. More than 90% of the children are now protected, and scientists estimate that it can prevent 5.4 million cases and 23,000 deaths in children younger than 5.

The vaccine is a scientific breakthrough that marks a major step forward as scientists work to eradicate the disease.

Sources: NY Times, BBC, Nature, NIH.gov