Jellyfish are often considered a nuisance because of how painful and potentially dangerous their sting can be to swimmers.

Jellyfish are often considered a nuisance because of how painful and potentially dangerous their sting can be to swimmers.

However, they are mesmerizing creatures to watch. Under neon aquarium lighting, flocks of softly undulating moon jellyfish (Aurelia aurita) make for a breathtaking display.

Scientists have been trying for years to uncover the secrets behind the effortless movement of these ocean invertebrates. In fact, studies show that jellyfish may be the most efficient swimmers on the planet and exert very little energy as they glide through the water. Let’s dive in to find out more.

How Do Jellyfish Move?

Back in 2013, Dr. Gemmell and his colleagues decided to study the unusual movement of jellyfish and identified two main phases.

Back in 2013, Dr. Gemmell and his colleagues decided to study the unusual movement of jellyfish and identified two main phases.

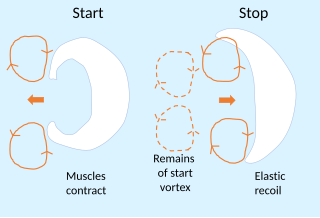

- During the first phase, a jellyfish contracts its bell, expelling water and propelling itself forward, similar to a rocket firing off the ground.

- During the second phase, the jellyfish slowly refills with water, preparing itself for a repeat of the cycle.

Seawater is much heavier than air, meaning that underwater animals have to adapt to constant pressure and resistance. To add to that, seawater is slippery, with no helpful surfaces to push off against. However, jellyfish are somehow able to boost themselves forward effectively and efficiently, without ever slowing down.

What surprised Dr. Gemmell and his colleagues in 2013 was that the jellyfish did not exert much effort during the refill stage. They expected that the jellyfish would slow down while refilling. But instead, the jellyfish were riding on the force of a mini, spinning ring of water. This tiny water vortex is created by the motion of the elastic tissue in the jellyfish’s bell, and gives it enough oomph to move forward.

A "Wall of Water"

In his latest study, Dr. Gemmell and his colleagues discovered yet another fascinating aspect of jellyfish motion.

In his latest study, Dr. Gemmell and his colleagues discovered yet another fascinating aspect of jellyfish motion.

Using high-speed video, they recorded the movement of eight moon jellyfish. They created a backdrop of illuminated glass beads which helped make the water vortices more visible.

As the jellyfish refilled, their bells created a rotating ring of water (vortex). And when they contracted their bells, they created a vortex in the opposite direction. When these opposing swirls of water collide, they create an invisible “wall.” By using this virtual wall to push off against and propel forward, the jellyfish move using very little energy!

Professor John O. Dabiri, a professor of aeronautics and mechanical engineering at the California Institute of Technology, has already thought of a possible application. Rather than building mechanical underwater robots from scratch to measure ocean conditions, the idea is to implant microelectronics, or tiny sensors, in jellyfish, turning them into living robots. From there, scientists can control the jellyfish remotely by stimulating their muscles and directing them to gather the data they need.

Sources: NY Times, Britannica, royalsocietypublishing.org, Science Daily, NewScientist, sciencemag.org