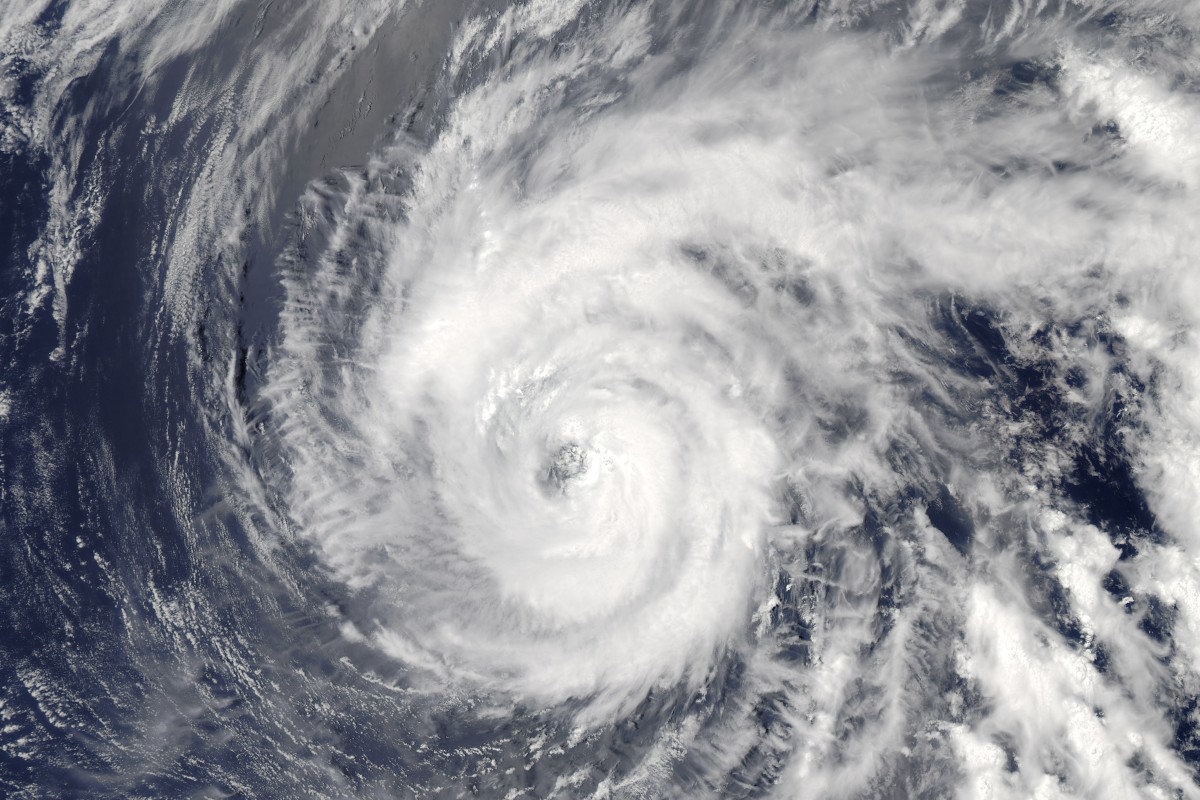

If you reside near a coast or on an island, you're likely familiar with hurricanes or typhoons.

If you reside near a coast or on an island, you're likely familiar with hurricanes or typhoons.

But did you know that hurricanes and typhoons are essentially the same phenomenon? They are just named differently based on their location: hurricanes in the North Atlantic and typhoons over the Northwest Pacific. Elsewhere, they're referred to as tropical cyclones.

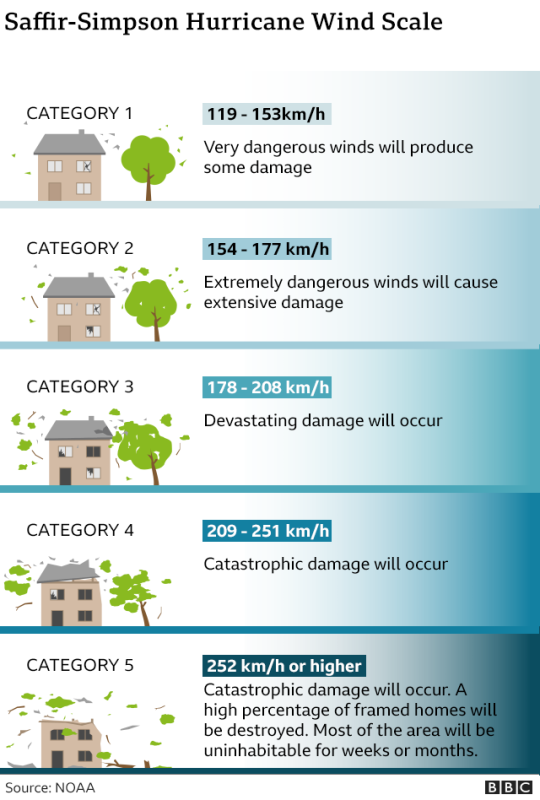

These destructive storms are classified on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale, a system that helps people understand the possible severity of impending storms.

Some scientists suggest adding a higher-ranked category to emphasize the destructive power of extreme storms. But what would this category be, and are there any storms that fit into this category? Let’s find out!

What Are the Hurricane Categories?

In the 1970s, Herbert Saffir and Robert Simpson created the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale, which consists of five hurricane categories.

In the 1970s, Herbert Saffir and Robert Simpson created the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale, which consists of five hurricane categories.

The scale has five categories, ranging from Category 1 (74-95 mph winds) to Category 5 (157+ mph winds) to warn residents. However, these categories only refer to wind speeds and do not account for other factors such as excess precipitation, tidal surge, or any offshoot storms. Unfortunately, these unmeasured factors, particularly storm surges and flooding, often cause more deaths than high winds!

Scientists are considering introducing a Category 6 for hurricanes with winds exceeding 192 mph. So far, we have seen five hurricanes that qualify as Category 6, which include Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines in 2013 (max wind speed of 195 mph) and Mexico’s Hurricane Patricia in 2015 (max wind speed of 214 mph).

The Debate

This idea is supported by prominent scientists such as Michael Werner at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, and James Kossin, science advisor for the First Street Foundation. Werner and Kossin argue that expanding the category system helps better communicate the potential danger and damage associated with powerful storms.

They contend that leaving the category threshold capped at Category 5 is troublesome because “it tends to understate the risk” from climate change. They’re using science to back their claims, citing that rising temperatures provide extra energy to fuel hurricanes and typhoons.

Critics, however, believe the focus on wind speed is insufficient. They suggest more in-depth categories, rather than additional ones. Deirdre Byrne, an oceanographer at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), suggests adding letter classifications to the Wind Scale to help warn residents of secondary storm perils.

Critics, however, believe the focus on wind speed is insufficient. They suggest more in-depth categories, rather than additional ones. Deirdre Byrne, an oceanographer at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), suggests adding letter classifications to the Wind Scale to help warn residents of secondary storm perils.

Other actions are also being taken. The National Hurricane Center (NHC) is upgrading its forecast cone to show how far a hurricane’s danger might reach. NOAA’s weather forecasters are drawing attention to hurricane offshoots, such as expected amounts of rainfall, possible mudslides, and more.

The debate on how best to classify and communicate the dangers of tropical cyclones continues. Both parties are concerned about the impacts of these storms. Hopefully, they will find a solution that reflects a balance between science and public safety!

Sources: Grist, The Conversation, NPR, NOAA, Washington Post, Red Cross